Containers (Docker): A disruptive force in cloud computing

One of the primary goals of any well designed software is to abstract the complexity and present a simple consumable solution to the problem. But what about the software development process itself? Modern day software development lifecycle has become tremendously complicated. The variety of software stacks and hardware infrastructures that applications run on these days has drastically increased.

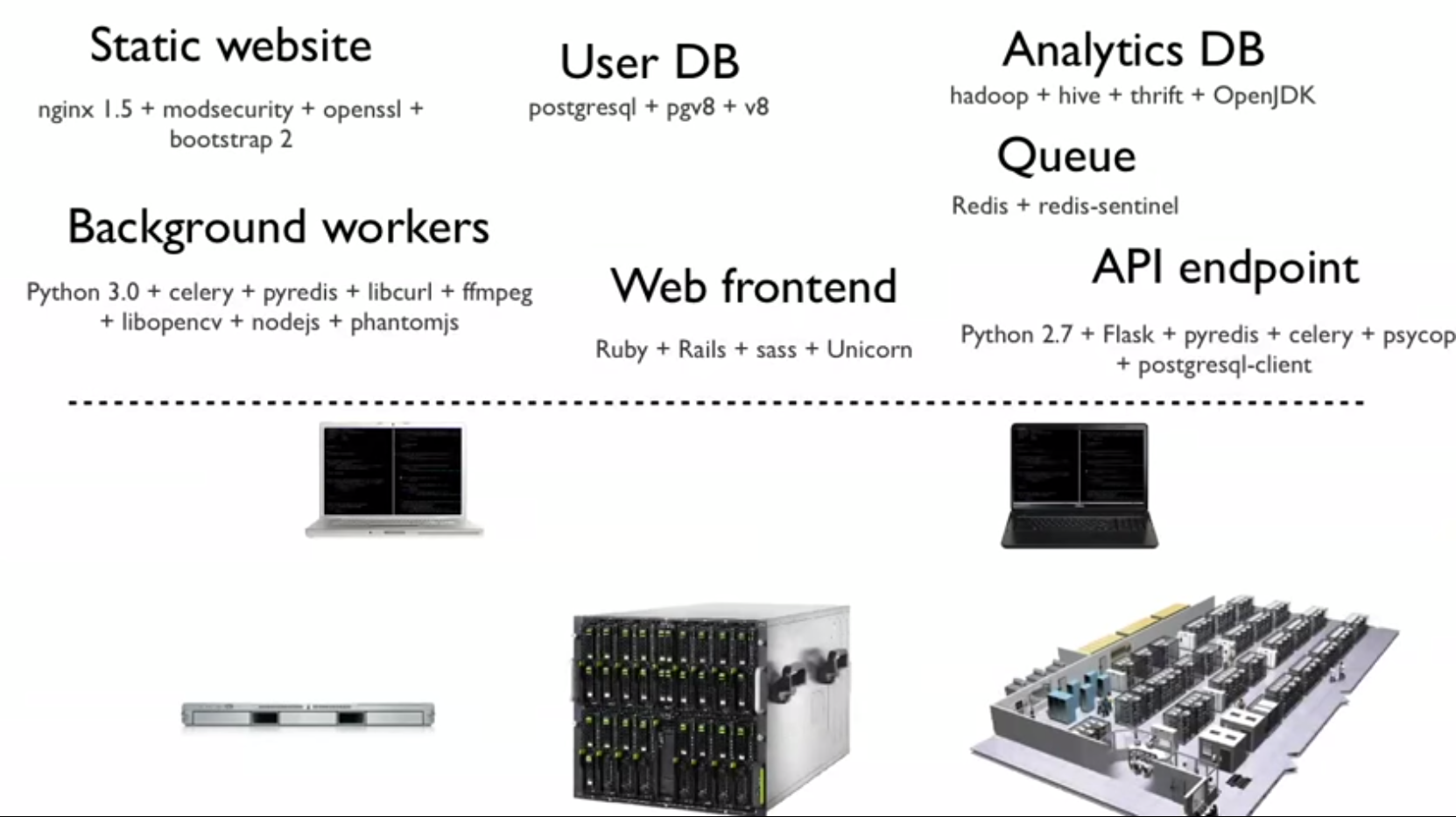

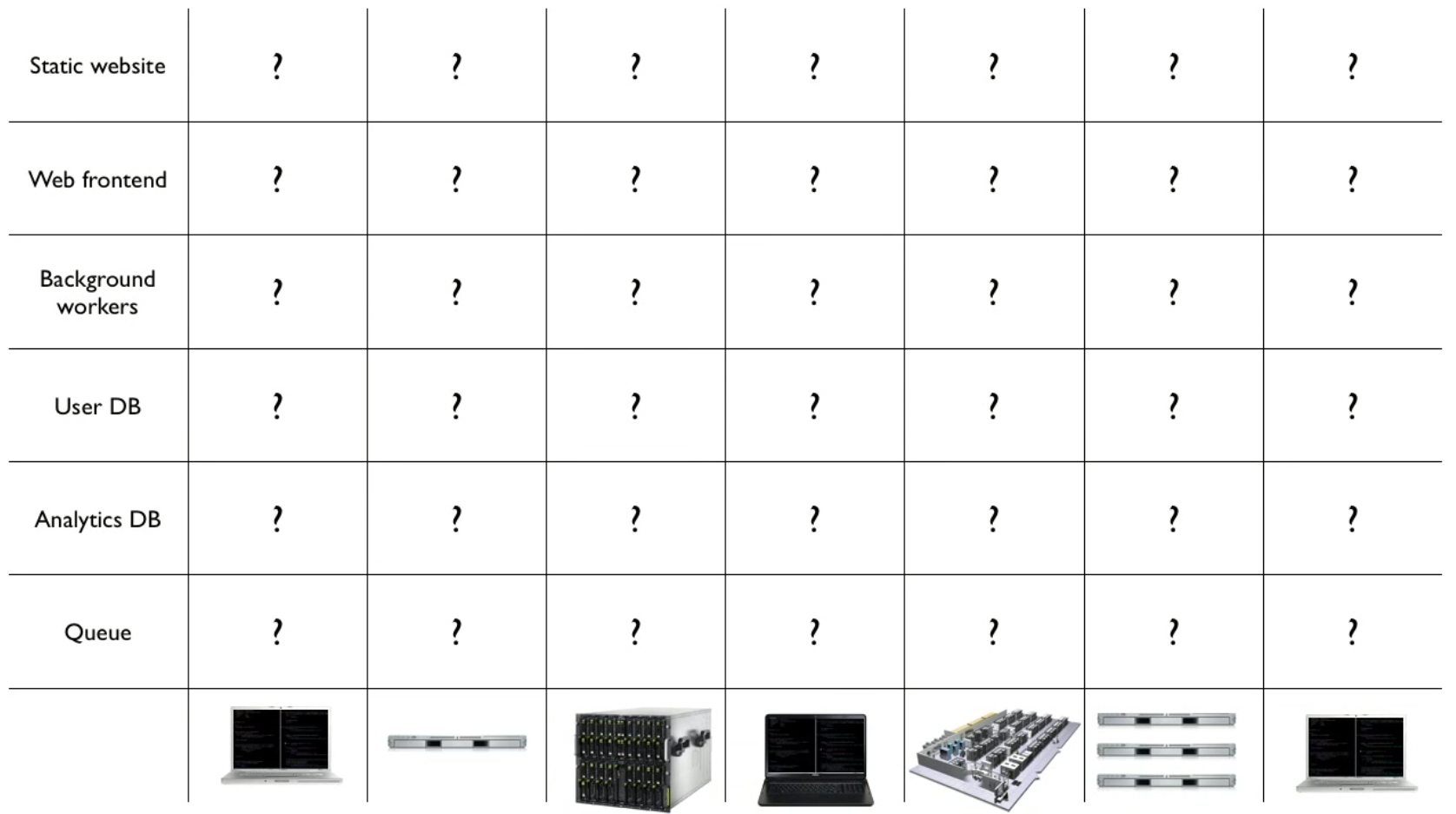

Even a simple web application is likely to have a back-end database server, application/web server, each potentially hosted on different hardware infrastructures with its own operating system. Bring in some more complexity and you have a scale-out deployment, load balancer/caching server, message broker, analytics DB and what not. Add to this the various software libraries and frameworks used for frontend/backend development and all their dependencies. And this whole thing has to run alike on different landscapes - developer systems, test systems and production/deployment landscape. Now bring in continuous integration and continuous deployment. You get the picture?

Although this can drive any DevOps person crazy, it is not just a DevOps issue.

One of the fundamental problems is:

“Shipping code to server is too hard”

It shouldn’t be! We, as software developers, are masters of hiding complexity. So why should we drown in a pool of complexity we created for ourselves?

Virtual Machines tried to address the hardware resource issue by abstracting the hardware from the operating system, and providing the ability to allocate chunks of computing resource as needed. The big benefit was server consolidation and better utilization of hardware resources.

But it did not solve the core problem stated above - easier shipment of code. How do we make it easier and faster to ship any software, running on any technology stack, and run it on any hardware infrastructure? How do we rid the world of the “But it works on my system!” excuse?

Enter Containers

Linux kernel allows running multiple isolated user space instances. A container is such an isolated environment where one or more processes can be run. Containers focus on process isolation and containment instead of emulating a complete physical machine.

Historically, chroot in Linux kernel has provided some level of isolation by providing an environment to create and host a virtualized copy of a software system, ever since early ’80s. But the term process containers didn’t come up until around late 2006. It was soon renamed to ‘Control Groups’ (cgroups) to avoid confusion caused by multiple meanings of the term ‘containers’ in the Linux kernel. Control Groups is a linux kernel feature available since v2.6.24 that limits and isolates the resource usage of a collection of processes. Subsequently, namespace isolation was added.

This lead to the evolution of Linux Containers (LXC), an operating system level virtualization environment that is built on Linux kernel features mentioned earlier, like chroot, cgroups, namespace isolation, etc.

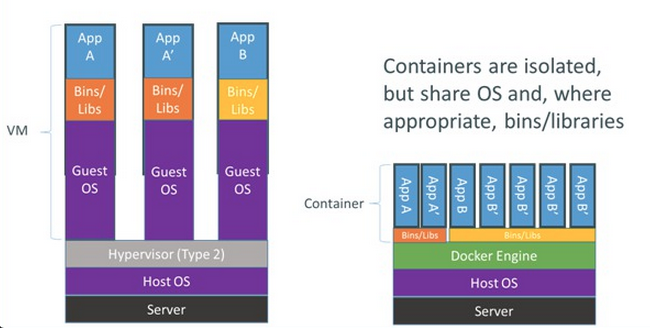

Before we go further, it is important to understand the difference between containers and virtual machines.

Containerization vs Virtualization

Virtualization is a software technology that separates an operating system from the physical resources. The Hypervisor running on the host operating system presents a complete set of hardware - CPU, memory, disk, etc - to the guest operating system, fooling it into believing that it is running on real hardware.

Containers offer an environment as close to possible as the one you’d get from a VM but without the overhead that comes with running a separate kernel and simulating all the hardware.

In containerization, also referred to as OS-level virtualization, the host and the guests share the same kernel. This approach reduces resource wastage since each container only holds the application and related libraries and binaries. The role of Hypervisor is handled by a containerization engine like Docker, which is installed atop the host operating system.

Operating-system-level virtualization is a server virtualization method where the kernel of an operating system allows for multiple isolated user space instances, instead of just one.

The main advantage of containers is that it is free of OS overhead, which makes it considerably smaller, easier to download and more importantly, faster to provision. This advantage also allows a server to potentially host far more containers than virtual machines. Scalability, portability, ease of deployment are some derived advantages.

I/O and memory performance levels of containers are much better compared to virtual machines; In fact very close to native performance.

But one major consideration when talking about containers is that all containers share the same base linux kernel. Your underlying operating system must be a flavour of linux. So, yes, linux only! If your application is windows based, you might have to turn to virtual machines.

OK! Let’s talk about Docker!

What is Docker?

Docker is an open platform for developers and sysadmins to build, ship, and run distributed applications.

Docker is an open source container orchestration engine that separates applications from their underlying operating system. In other words, it is commoditized LXC.

You get all the container benefits discussed earlier that LXC provides. In addition, Docker offers the following on top of LXC:

-

Application-centric: Docker is optimized for the deployment of applications, as opposed to machines.

-

Portable deployment across machines: Docker defines a format for bundling an application and all its dependencies into a single object which can be transferred to any Docker-enabled machine, and executed there with the guarantee that the execution environment exposed to the application will be the same.

-

Automatic builds and versioning: Docker provides a tool for developers to automatically assemble a container from source code. With Git like capabilities, containers are versioned, with their history maintained, providing options to commit new versions or rollback.

-

Component Re-use: Containers are re-usable components. Any container can be used as the base to create specialized components.

-

Sharing: Docker Hub acts as a public registry where containers can be shared.

-

Tooling: Apart from the client tools provided with Docker, Docker defines an API for automating and customizing the creation and deployment of Containers, which has opened up Docker tooling to the ecosystem.

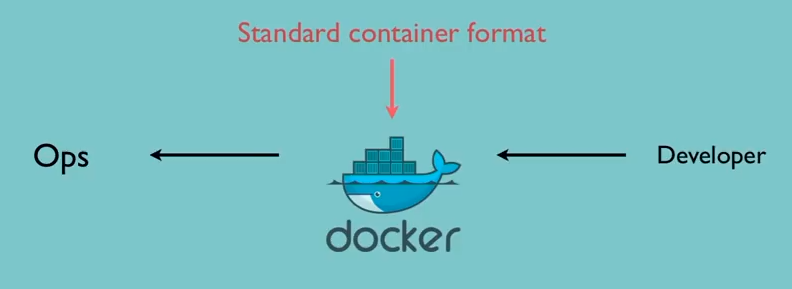

The goal of Docker is to act like a standard shipping container for software. The developer packages a container with the required software and its dependencies. The DevOps and infrastructure team manages and deploys the container.

The differentiator for Docker, as against standard Linux Containers, is that it treats containers as a unit of software delivery - or an envelope for running an application. So the commands and API calls are all process oriented. Here it is important to note that Docker runs 1 process per container, which is a major difference from other container engines like Warden.

Docker started off running on top of LXC as its execution engine. But since v0.9, it has dropped LXC as the default engine and replaced it with its own libcontainer. By doing so, Docker has decoupled itself a little from linux dependency and could potentially have the capability of running on any operating system that supports some sort of environment isolation.

How do I run Docker?

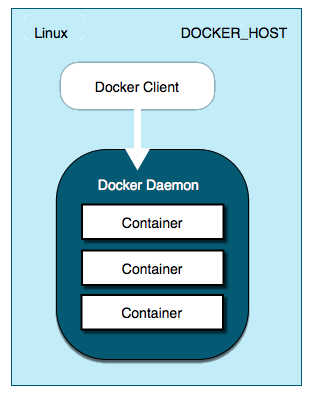

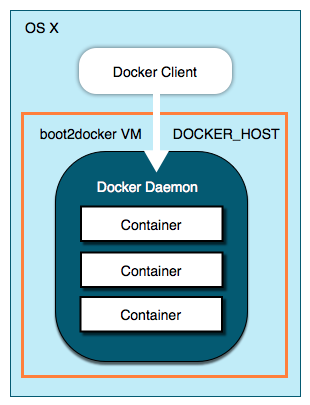

On a Linux system, you can install Docker and get started right away. It can conveniently use your host linux kernel and run containers on top of it. But if you are running OSX or Windows, you will need a virtual linux system to run docker off of. To make it easier for you, Docker provides a bootstrap called boot2docker, which is essentially a virtual linux distro (Tiny Core Linux) with Docker pre-installed. boot2docker boots off of Virtual Box and provides you the required environment to run the Docker Engine.

| Docker on Linux | boot2docker on OSX |

|---|---|

|

|

Docker components

Docker creates containers out of images, which are basically just tar balled file structure. Once a container is created out of an image, you can package applications and its dependencies into it, run a process/daemon/service on it, and keep the container running as long as you want the process to run. (The inverse is true as well: the container runs as long as the process is alive)

You can also commit the changes you’ve made in your container back to the image, which is versioned and layered. Docker also provides an online registry called ‘Docker Hub‘ where you can push and pull images from. It acts as a central build infrastructure and image sharing repository.

- Container: an application sandbox

- Image: a static snapshot of the containers’ configuration

- Registry/Hub: a repository of images

- Dockerfile: a configuration file with build instructions for Docker images

- Docker Compose: tool for defining and running complex applications with Docker (Formerly Fig)

Containers and PaaS

Everything at Google runs in a container.

Google starts over 2 billion containers per week.

— Joe Beda, Google Cloud Platform

Containers have been the back-bone for PaaS solutions for years now. Almost every PaaS in the market now uses some form of Linux Containers. Just that the technology was abstracted from the developers or PaaS users. But with commoditization of Containers in the form of Docker, Warden, etc. opportunities have opened up for developers and dev-ops to better manage and control the deployment and scaling of applications.

In fact, experts say PaaS is evolving into 2 flavors:

- PaaS by Service Orchestration

- PaaS by Container Orchestration

The latter is gaining focus with commoditized container orchestration technologies. Docker is acting as a disruptive force that is forcing people to rethink many of the layers of a cloud stack - starting from configuration management, networking, build, deployment and even microservices.

A good PaaS needs more than Virtual Machines to run on

If you turn around the perspective and look at it from Docker/Container point of view, many believe that without PaaS, Docker is just a bunch of containers. The advantages of Docker are realized when used in an enterprise cloud stack or PaaS environment. The ease of deployment and portability make containers an essential part of PaaS.

In spite of all the debate and discussions, I believe PaaS and Containers like Docker are not competing technologies, but rather complementary. In fact this elastic mesh of containers composing an Application is what makes PaaS so efficient.

Docker, having gained some momentum among container technologies, is important for the future of PaaS. To ignore it in a PaaS would be suicidal. Few sections below in this post, I’ve written how even Cloud Foundry, which has its own container engine, is embracing Docker.

Containers and Micro-services

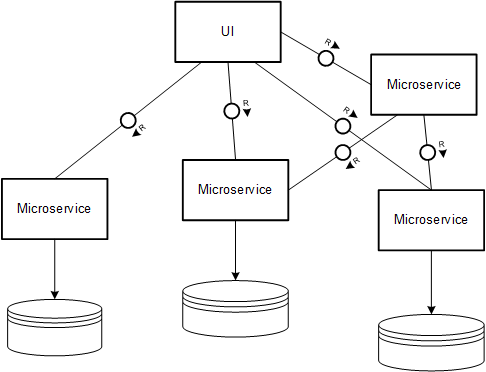

Microservices, is the new kid in the block, and is considered the next big thing in software architecture. You can look at it as ‘fine-grained SOA’ - an approach to developing an application as a suite of small services, each running in its own process and communicating with each other using some light-weight mechanism, with independent deployments, scalability and portability. You should already see how Containers just perfectly fits into that context!

Container brings in the isolated process space, with managed deployments and scaling. They are a very good fit for acting as deployment units for services. The orchestration capabilities, especially deploying, updating and scaling of containers independently is a perfect fit for microservices architecture.

One of the main complexities of a microservices architecture is in managing/operating a distributed set of services. To address this, a bunch of frameworks have evolved with the primary goal of simplifying the management of services/containers in a cluster/distributed environment. Google’s open source project Kubernetes is gaining a lot of traction. There is Apache Mesos, Fleet and few others as well. Kubernetes acts as an orchestration engine for containers, taking care of the scheduling and deployment onto nodes in a compute cluster and managing workload. Another important aspect of microservices that frameworks like Kubernetes addresses is service discovery and fault tolerance.

I’ll probably need a separate blog post to discuss Microservices in detail. Hope to roll out a post soon.

Other Container Engines

Warden

Warden manages isolated, ephemeral, and resource-controlled environments.

Warden is the container orchestration engine for Cloud Foundry, which exposes APIs for managing the isolated environments. All applications deployed to Cloud Foundry runs within a Warden container. It constitutes a warden server and a ruby based warden client. The server and client interface using Google protocol buffers.

Warden differs from Docker in few aspects. It supports multiple processes in one container as against a single process in Docker. Warden also provides higher control over the resource isolation as compared to Docker. Where Docker beats Warden is with its re-usable/layered image or container management, along with hub based sharing.

Synergies between Warden and Docker

There has been a lot of discussion and traction on having Warden work with Docker. Since Docker moved from LXC to its own libcontainer, basing a new Warden Linux backend on libcontainer has become a possibility. Cloud Credo which provides Cloud Foundry expertise and services came up with Decker, which uses Docker as the backend to Cloud Foundry.

But the most promising integration with Docker is seen in the new Cloud Foudry elastic runtime - Diego. Written in Go, Diego is the new orchestration manager for Cloud Foundry. It is a collaborative open source effort between Pivotal, IBM, SAP and Cloud Credo.

Rocket

Rocket is a container runtime built by CoreOS. Although CoreOS was actively involved in the Docker development, they were not happy with Docker moving from being a ‘standard container’ to a container platform, which is why they have started Rocket. The goal is to keep the focus on providing a standard container that is content-agnostic and infrastructure-agnostic, although I don’t see the point. What is even more suprising is that Rocket is not a fork of Docker, but a rewrite.

Spoon

Spoon provides containers for Windows. It runs containers on top of Spoon Virtual Machine installed on a host windows system. It has a strange 1:1 analogy to a lot of Docker’s concepts like containers, images, hub, etc.

Drawbridge

Drawbridge is a Microsoft research prototype experimenting on ‘picoprocess’ - a process-based isolation container, which can run something called a ‘library OS’ which is lightweight Windows OS capable of running in a picoprocess.

In my next post, I plan to demonstrate some of the container concepts discussed here with an example based on Docker. Stay tuned!